Este es el primero de una serie que conversatorios que se realizarán para crear conciencia sobre la labor de los intérpretes de conferencias que trabajan para órganos jurídicos nacionales o internacionales.

Los organismos que velan por los Derechos Humanos (DD. HH.) en América son dos.

La Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, con sede en Washington (EE. UU.), monitorea la situación de los DD. HH. en los países del continente, analiza los escenarios que viven los migrantes, los privados de la libertad, la población LGTBI, y los afrodescendientes, entre otros grupos vulnerables.

Por su parte, La Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (Corte IDH), que tiene sede en San José de Costa Rica, entiende en los casos remitidos por la CIDH. Solo en 20 de los 33 estados integrantes de la Organización de los Estados Americanos la Corte IDH tiene jurisdicción. Sobre el resto tiene competencia la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Todo procedimiento debe comenzar por la Comisión que procesa la denuncia para que luego pueda proceder a la Corte. Esta es una diferencia con Europa donde hay acceso directo del individuo el Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos. ¿Cuál es el impacto, entonces, de la Corte IDH? «La fortaleza que tiene el sistema interamericano es que son pocos casos, aunque de alto impacto», sostuvo el Secretario, Dr. Pablo Saavedra Alessandri.

Una de las contribuciones del organismo es el concepto de la reparación integral. «El resultado del trabajo que hacemos en la Corte lo podemos ver en las personas y en el impacto estructural que se genera (…) Para las víctimas, que las escuche la Corte ya es una reparación en sí misma».

Antes se pensaba que la violación de DD. HH. se compensaba con una reparación económica a favor de las víctimas. «Pero un sistema de DD. HH. no puede construirse sobre la base de una concepción de ‘matar-indemnizar’ porque el daño sufrido por esa persona o esa comunidad es mucho más profundo. Entonces, se desarrolló el concepto de reparación integral», explicó Saavedra Alessandri.

La reparación integral

Este concepto significa que no podemos considerar una indemnización económica solamente. Se le brinda a la víctima atención a la salud, apoyo psicológico y psiquiátrico, contención emocional. En algunos casos, como los de las comunidades indígenas, se pide volver a la situación anterior restituyendo las tierras o bienes expropiados ilegalmente o dando la libertad a quienes han sido privados de ella.

Otro tipo de reparación es la que denominamos “satisfacción”; por ejemplo, pedir perdón públicamente, hacer un documental, un libro o erigir un monumento en homenaje a las víctimas. «Y los Estados lo cumplen», sentenció el abogado.

La gran contribución que hace la Corte IDH es que se pueden llegar a solucionar un problema estructural, resolviendo además muchas cuestiones conexas gracias a las garantías de no repetición. Es así que los hechos que originan una violación de los derechos son extirpados del ordenamiento jurídico.

Casos emblemáticos individuales que cambian la realidad de millones

La resolución de un solo caso puede tener un impacto estructural. He aquí algunos ejemplos:

Masacre en Perú: Hubo una matanza de estudiantes en Perú durante el gobierno de Alberto Fujimori. Se dictó una ley de autoamnistía que prohibía cualquier persecución penal por violaciones de DD. HH. que hubieran cometido las fuerzas armadas entre 1980 y 1995. Este caso llegó a la Corte IDH y se entendió que las leyes de amnistía carecían de validez por ser contrarias a la Convención Americana sobre Derechos Humanos. «Lo que hicimos fue propiciar un terremoto en el ordenamiento jurídico», recordó Saavedra Alessandri. Perú implementó las decisiones de la Corte y se generó un cambio absoluto, y así se desmanteló el andamiaje de impunidad; y los responsables están privados de la libertad.

Fecundación in vitro en Costa Rica: En el año 2000 se prohibió la fecundación in vitro en Costa Rica. Había parejas que ya habían empezado con el tratamiento y no podían continuar. La Corte IDH determinó que el gobierno debía «permitir y regular la fecundación in vitro. Y lo hizo, dictó un decreto. Así, muchas parejas han podido optar por ese tratamiento».

El caso Awuas Tingni contra Nicaragua: En esta comunidad no solo el idioma es una limitación; la interpretación con respecto a los derechos también presenta diferencias. Esta comunidad tiene un concepto de propiedad comunal, es decir que los bienes pertenecen a toda la comunidad y no a un individuo. La Corte IDH se inclinó por proteger esta concepción, y se instó al gobierno de Nicaragua a «reconocer la propiedad comunal y ancestral de acuerdo a la cosmovisión de las comunidades indígenas». A tal fin, se creó un mecanismo de delimitación de la propiedad y esto, a su vez, repercutió en cientos de comunidades y resolvió un problema estructural de todo el país.

Desaparición forzada en México: El organismo tomó conocimiento de la desaparición forzada de personas y de mujeres indígenas violadas por las fuerzas de seguridad en un país de la región; y que las causas iban a ser juzgadas por los tribunales militares. La Corte definió que no se podía aplicar la jurisdicción militar, sino que debía ser un juzgado civil el que entendiera en la causa. Como resultado, se cambiaron los criterios de interpretación relevantes a estos casos para pasarlos al fuero civil; y se cambió la ley federal de México para hacerla compatible con esta decisión.

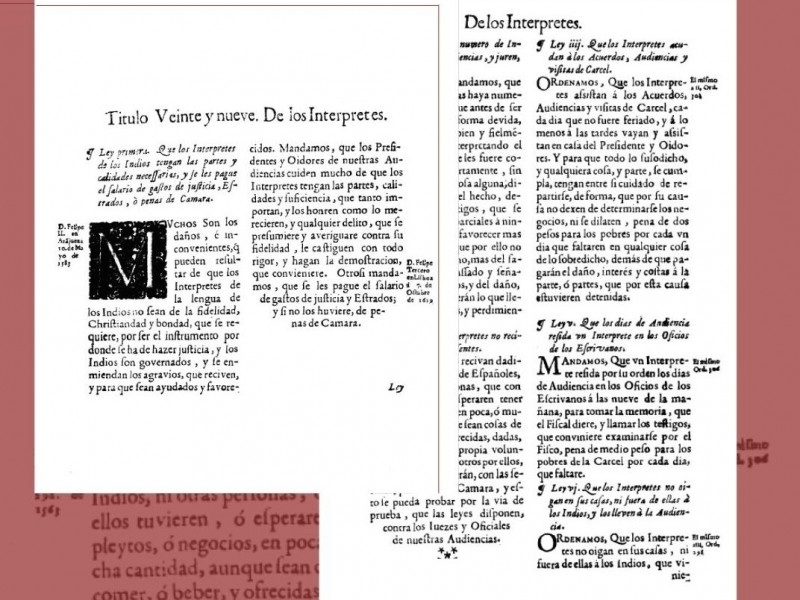

Cómo trabajan los intérpretes en la Corte

Las actuaciones en la Corte IDH se realizan en los idiomas oficiales de la OEA: español, inglés, portugués y francés. Cada caso se tramita en el idioma del país al que pertenece. A veces, existen peritos que solicitan hablar otro idioma y el organismo provee el intérprete. Por ejemplo, respecto de comunidades indígenas que no hablan español, «Recibimos un caso de una comunidad de Surinam, donde se hablaba el ndyuka. Tuvimos que conseguir un intérprete propio de la comunidad que lo tradujera al holandés, de allí al inglés, y finalmente, del inglés al español. Para nosotros es esencial que las comunidades indígenas hablen su propio idioma».

En el último caso mencionado en el apartado anterior, en particular, se destaca la tarea realizada por los intérpretes. Según el art. 8 de garantías judiciales del Pacto de San José de Costa Rica «toda persona tiene derecho a ser asistido gratuitamente por un traductor o intérprete, si no comprende o no habla el idioma del juzgado o tribunal». Las dos mujeres indígenas no hablaban bien español, y al principio, no se les permitió hablar en su lengua. La Corte sostuvo que la traducción en su idioma era garantía esencial del debido proceso. Esto generó un gran cambio en México y ahora las comunidades pueden expresarse en su propia lengua tanto en procedimientos administrativos como judiciales.

Nuestra colega Sharona Wolkowicz, intérprete del evento, señaló que el trabajo en la Corte IDH supone retos de distinta índole. Por una parte, el intérprete debe estudiar los conceptos jurídicos y el vocabulario técnico correspondientes a cada país y buscar una versión adecuada en la lengua meta. Para ello, se deben tener en cuenta los dos sistemas jurídicos existentes en la región (el Derecho Romano Germánico y el Common Law), lo que a menudo exige recurrir a explicaciones parafraseadas, además de una gran inversión de tiempo y esfuerzo en investigación y estudio.

Además, los casos ventilados en la Corte IDH suelen tener una carga emocional muy fuerte, que impone al intérprete el desafío de mantenerse incólume ante relatos desgarradores. En esta ocasión, Sharona compartió con nosotros una anécdota dolorosa. Cuando estaba embarazada, le tocó interpretar el testimonio de un hombre cuyos ahijados — dos muchachos adolescentes— habían sido torturados y asesinados por agentes del Estado. De pronto, pese a sus esfuerzos, se sintió embargada por una emoción tan fuerte que tuvo que abandonar la cabina, dejando la interpretación en manos de su colega, quien la conminó a ausentarse por algunos minutos para que recuperara la compostura.

Conclusiones

«A pesar de que pueden parecer pocos casos, el trabajo de la Corte tiene mucho impacto en la región. Es una voz de esperanza para miles de víctimas, tiene un alcance generalizado y estructural, y está produciendo un empoderamiento de nuestra jurisprudencia en los diferentes actores, tanto estatales como de la sociedad civil, para producir un cambio en la efectiva protección de DDHH», resumió el Dr. Saavedra con satisfacción. La Corte IDH vela por los derechos de los habitantes de toda América y, en cada sentencia, marca un camino que cambiará la realidad de muchos.

Los intérpretes y traductores en el campo jurídico/judicial no solo deben traducir términos sino moverse con holgura entre sistemas de derecho tan diferentes como el Common Law y el Derecho Continental.

Agradecemos al AIIC Legal and Interpreting Committee por esta iniciativa que contribuye al esclarecimiento de las diferencias entre sistemas jurídicos para beneficio de los intérpretes que se desempeñan en los diferentes fueros judiciales, y para la sociedad en su conjunto, ya que todas estas acciones contribuyen a la mejora del debido proceso.